The most important change to the US demographics over the next 20 years will be the decline of non-Hispanic whites, and the rise of the overall Hispanic/Latino population. The US will be ‘minority white’ by 2045.

This will have tremendous effects on Christianity in the US. Latino theologians bring an incredibly diverse and rich view to Christianity, but the most influential thread of Latino theologians in Christianity is without a doubt, Liberation Theology and its “preferential option for the poor”. Liberation Theology is pregnant with the future of American Theology stemming from a long history of Jesuit priests and missionaries in the Americas.

The seminal work on Liberation Theology is “A Theology of Liberation” by Gustavo Gutierrez (published in 1988 by Orbis Publishing). Its the Wealth of Nations or the Declaration of Independence of Liberation Theology. I haven’t found a palpable summary of the text, so here is my attempt.

A Theology of Liberation by Gustavo Gutierrez

Gutierrez writes that in history there are three phases of theology in history: wisdom, rational knowledge, and the third, and most recent, is theology of critical reflection on praxis. The book is devoted to this third phase of theology which has come to be defined as Liberation Theology. The three phases are:

- Theology of Wisdom: This is seen as the spiritual element of theology, heavily influenced by the Greek philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, etc.

- Theology of Rational Knowledge: This is the phase that was “born at the meeting of faith and reason.” Heavily influenced by St Thomas Aquinas and the idea that theology is an exercise in reason and makes logical sense.

- Theology of Critical Reflection on Praxis: This is the stage that creates a “fruitful synthesis between contemplation and action.” It was heavily influenced by St Ignatius (founder of the Jesuits). The theology accentuates the ‘spirituality of the laity’.

The Problem:

Gutierrez claims the church in the past did not sufficiently discuss the political and power structures of the world. After the social movements of the 60s, the gap between the oppressed and the oppressor has only grown rather than decrease as was expected. “It is only in the last few years that people have become clearly aware of the cope of misery and especially of the oppressive and alienating circumstances in which the great majority of humankind exists.”

Instead, the church “devoted its attention to formulating truths and meanwhile did almost nothing to better the world… and left ‘orthopraxis’ in the hands of nonmembers and nonbelievers”.

What is at stake is the further suffering of the world and “the possibility of enjoying a truly human existence, a free life, a dynamic liberty which is related to history as a conquest.”

The Vision:

Gutierrez explains that the church’s role is to be the “soul of human society”. The future could be “liberation – a free gift from Christ – is communion with God and with other human beings.”

The most powerful portion of the book for me was this part about repentance. Gutierrez reads a statement from a group of Peruvian priests made after the famous Vatican II and subsequent Medellin Conference. The priests confess their complicity in the problems in the world today as a requisite posture for the future of liberation. They said, the church “attempts to assume it’s responsibility for the injustice which it has supported both by its links with the establish order as well as by its silence regarding the evils this order implies”.

But this book isn’t just about the powerful coming down to help the oppressed, rather the “process of liberation requires the active participation of the oppressed… it is the poor who must be the protagonist of their own liberation.”

To Gutierrez, Latin America is the prime example for this liberation as an oppressed region to the colonial European powers and the United States. His call for a future is “one in which man is defined first of all by his responsibility towards his brother and toward history.”

The Theology:

The overall argument here is that our lives aren’t a “trial-run” for an after-life, but rather salvation underlies everything we live now. Salvation is “the communion of human beings with God and among themselves.” He references Matthew 25 as the example of how we reject God by turning “away from the building up of the world, do not open ourselves up to others, and culpably withdraw into our selves.”

The work of transforming the world and building human community is a salvific work that represents the God of Exodus who said, “I am who I am” which actually can be translated to “I will be who will be.” As the church, we are to build what God already is.

Gutierrez also argues that “an unjust situation does not happen by chance there is human responsibility behind it… Sin is not considered an individual private or merely interior reality. Period. Sin is regarded as a social, historical fact, the absence of fellowship and love in relationships among persons, the breach of friendship with God and other persons, and, therefore, an interior, personal fracture.”

The Future:

Gutierrez vision is one in which the church places itself in the path of the oppressed because the “future of history belongs to the poor and exploited. True liberation will be the work of the oppressed themselves; in them, the Lord saves history.” When we find “social, political, economic, and cultural inequalities, there will we find the rejection of the peace of the Lord and a rejection of the Lord himself.”

He argues that liberation and salvation work is not just for believers and the church, but rather for all of mankind. “Since the incarnation, humanity, every human being, history, is the living temple of God. The ‘profane’ that which located outside the temple, no longer exists.”

One final note is the fact that the eucharist in John’s gospel replaces the supper with the washing of feet. This sacrament he sees as a call to “communion with God and to the unity of all humankind.”

In my opinion, future Christians will have a preferential treatment for the poor and be more actively engaged in government organizations for charity rather than private organizations. Christians will be more engaged in city governments where the oppressed are often being hurt the most rather than staying in church organizations. I think these are positive changes.

If you enjoyed this content, subscribe here to my newsletter to receive future articles.

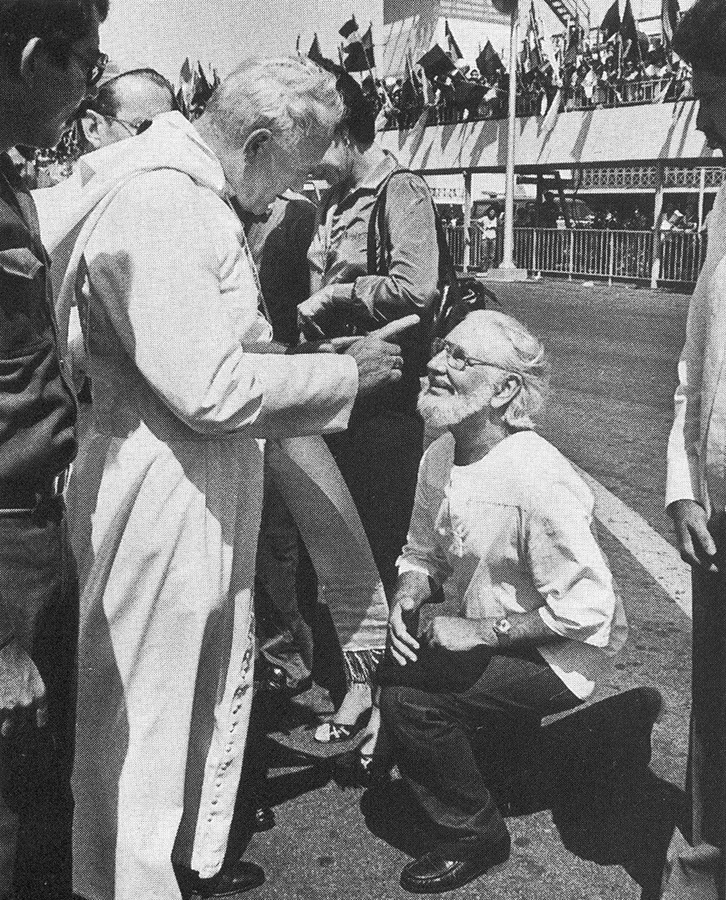

his finger and publicly reprimands Liberation Theology

Jesuit priest and Sandinista Minister of Culture

Ernesto Cardenal.