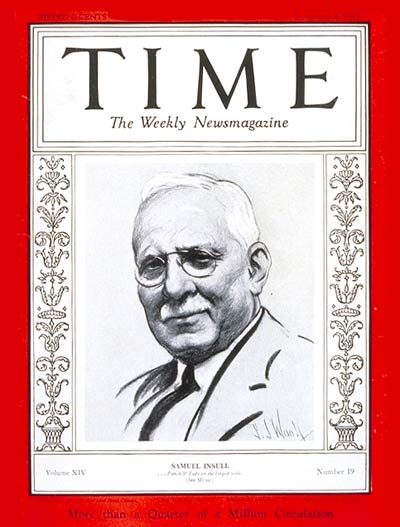

From personal secretary to the “Henry Ford of electricity” to the “World’s Greatest Failure”, the life of Samuel Insull is nothing short of interesting.

I came across Insull because he is one of Chicago’s most successful businessmen of all time and eventually became the largest producer of electricity in the world. (I live only a few minutes from his company’s now-abandoned power plant, which was once the largest in the world) Insull stands out because of the way he cleaved to a great mentor, focused on practicality versus idealism, and ran a monopoly that served the customer with low prices rather than running a monopoly in order to raise prices.

Samuell Insull (Jr) was born in London in 1859 to a working-class family. His father (Sr) was never successful in his business ventures, but got a secretary job with a temperance movement organization called the Oxford Kingdom Alliance. Because of this job (Sr) held for eight years, his father was able to afford to send Insull (Jr) to a great London private schooling that exposed him to the biggest ideas of the day.

Insull (Jr) had a falling out with his father, and supported by his mother, got a job at age 15 at an auction-house. He developed skills of a secretary, especially penmanship thanks to a great mentor who was very tough on him. He eventually started working for the man who represented all of Thomas Edison’s interests in Europe, and Insull began a fascination with the great inventor. At 21 years-old, Insull was offered to be the personal assistant of Thomas Edison. He left all he knew in London and started a new life in the US.

This is one of the best lessons in business, to cleave to great mentors. By associating so closely with Thomas Edison at the height of his growing influence, Insull was following closely a lesson from Tony Robbins called the Power of Proximity. He cut decades of growth into days by meeting with most of the great businessmen of that time through Edison. Not only was Insull able to meet them, but by the age of 25 he had dealt with them as near-equals. He became so close to his mentor that when Edison’s first wife died early, the young Insull was devastated and said he felt like he had lost a mother in his life.

Insull didn’t try and nickle-and-dime his newfound boss either. When Edison asked how much he wanted to make, Insull simply let Edison pay what he wanted (which was about 1/2 of what he had previously been making). However, within that first year, that sum dramatically increased far beyond the wealth he had ever imagined. Insull is quoted as saying, “If you pushed Edison in money matters, he was stingy as hell, but if you left the matter to him he was generous as a prince.” This is fantastic advice when dealing with a great mentor.

Eventually, every great mentee will want to prove themselves and venture off on their own. For Insull, this opportunity came when he was offered the job to take over as Vice President over Edison’s interests in Chicago. It was a technically a huge demotion in terms of pay and size of organization. However, the upside was exciting with numerous fragmented small companies that Insull planned to join together in industrial tycoon fashion in a city John D Rockefeller called “the center of the empire.”

Insull had always been held back by Edison’s idealism and stubbornness, such as his refusal to use the superior AC versus DC technology because of personal interests. In Chicago, Insull had great freedom to put a more practical approach to business into place.

Insull’s first great discovery was that charging a flat amount was horrible for customers. He invented a meter system, that allowed individual customers to only pay for their own consumption. This invention drastically decreased prices of electricity for most customers by almost 1/3, and accelerated his company’s growth. This idea fueled his game-changing mentality on the electricity business to target mass markets rather than elite markets.

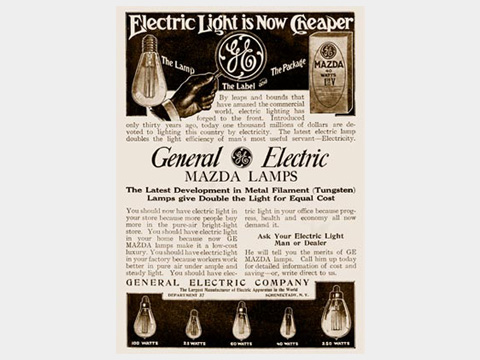

Most electric companies tried to build their monopolies with the wealthy where, once they owned the market, they could jack up the prices. Insull instead believed he could solve a great problem for the masses and charge the lowest possible price, therefore owning the entire market outright. His idea was extremely successful, and he built the first modern metropolitan supply network.

Electricity exploded. The number of electricity customers grew from 3.8 million to 23.8 million from 1912 to 1932 and generating capacity for electricity grew from 5.1 gigawatts to 34.4 gigawatts over that same time frame. Insull’s holding company grew from $1.1 Million (USD) in 1892 to $2.2 Billion (USD) in 1930 and from 400 employees to 72,800 employees over the same time-frame. People’s lives were drastically improved. With electricity, what some called “the modern emancipator”, people’s days were literally lengthened and kitchen sizes shrunk because the need for so many servants was reduced.

Insull became the largest producer of electricity in the world with his holding companies that owned hundreds of smaller electric companies, which included the largest power plant in the world. The secret was getting the every day person to believe they could afford electricity. Insull and his companies would even give away electrical appliances in order to increase demand for electricity. Their ads constantly educated on the importance of electricity.

Insull’s belief in the importance of the common man was even present in his philanthropy. When he built the Chicago Civic Opera House, he demanded that all the opera boxes for the wealthy be placed up high, at the back, so the common and poor attendees would not be able to see them. This was a stark contrast to the great opera houses of the day that had the boxes lording over the general public at the sides.

Insull’s story had a dramatic ending after the great depression when businesses started demanding Insull’s companies pay their bills. His holding companies only had $27 million in equity, which was mere fractions of what was owed. His business empire quickly unraveled, and on June 6, 1932, Insull resigned from 65 chairmanships, 85 directorates, and 11 presidencies over the period of three hours. He was eventually acquitted of all charges of fraud by a jury, but his mission to be an advocate to the common man was devastated.

Not only did he die with just 84 cents in his pocket and a lost business empire, he had over 600,000 investors in his company that lost everything they had invested with him. The New York Times recently called it, “The Enron Before Enron.” The guilt of letting down the common man that he had lived to serve, and whose money had funded his success, I think killed him. Just three years after he was acquitted of the fraud charges, Insull died of a heart attack on a public subway in Paris, France. He died seeing himself as a poor man.

References

- “Insull: The Rise and Fall of a Billionaire Utility Tycoon” by Forrest McDonald

- https://www.nytimes.com/1983/01/10/obituaries/samuel-insull-jr-82-son-of-utility-magnate.html

- https://www.ge.com/in/about-us/history/1878-1904

- https://www.ge.com/reports/from-appliances-to-apps-ge-to-sell-its-appliances-business-to-haier-for-5-4-billion/1928-refrigerator-ad-300-dpi/

- https://www.classicchicagomagazine.com/sam-insulls-turbulent-home-life/

- https://www.luc.edu/media/lucedu/archives/pdfs/insull1.pdf

- https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2013-07-14-ct-per-flash-samuel-insull-0714-20130714-story.html