In the 1800s, the United States had thousands of boats importing agricultural products from tropical climates in the Caribbean and Southern states. These ships would then return on their long voyages back to the hot climates completely empty.

To Frederic Tudor, the New England son of a famous attorney, this looked like a massive opportunity. What could he put in those empty ships that the hot climates needed? Ice.

Tudor developed a $200+ Million annual business (+$3 billion by today’s standards) by shipping ice to tropical climates around the world. In a time when air conditioning didn’t exist, ice for drinks was rarely an option, and trips between countries took months, Tudor achieved the impossible and brought ice to the tropics.

His story is filled with imprisonment, Caribbean voyages, entitlement, and frugality. His story is a lesson in the ultimate use of unused resources to make a profit.

Frederic Tudor was born in New England in 1783 to a wealthy lawyer who worked directly for John Adams. He grew up right next to the Massachusetts State House and lived near John Hancock and other Boston elites in Beacon Hill.

I first got interested in Tudor because I thought it was fascinating someone could become a millionaire by exporting ice around the world. I was shocked nobody had been successful before him at doing it, but ice was really just a burgeoning industry at the time even in cold climates. When I read how wealthy Tudor grew up and the incredible access he had, I immediately got turned off to him. I like hearing the stories of the struggle and difficulty, not just about folks who got handed wealth.

Tudor surprised me though. He got offered to go study at Harvard at 14 years old, but instead decided to work for his family’s furniture exporting business. On a trip to Cuba when he was 17-years old, someone gave him the idea to ship ice to the Caribbean. At his wealthy New England home, they would hold huge quantities of ice in barns during the summer in order to make ice cream and cold drinks, so this seemed like a great idea.

He got a ship, and took his first trip with ice to the island of Martinique. The ice arrived intact, but nobody would buy the ice, and he lost thousands of dollars. In fact, Tudor’s ventures proved so difficult that he was arrested and jailed more than once by debtors, and didn’t even make a profit until he was in his 40s.

Reading about young Tudor reminded me of a guy that I started my career with. He was the son of a very wealthy lawyer in Chicago and was very spoiled. We were both 22 years old starting our first jobs out of college. It was a grueling sales job that required hundreds of weekly cold calls. My colleague would often take long morning or afternoon breaks and go to the neighboring sky-scraper penthouse where his dad was a partner and lay on his father’s comfortable couches for naps.

My colleague was consistently lacking against his peers in sales, and eventually decided to leave to pursue his idea of starting a lifestyle business selling beef jerky. He got a bunch of capital from his wealthy father and friends in order to start his beef jerky venture that eventually failed.

To me, Tudor’s idea almost sounds like a cute, ‘lifestyle’ business, and every indication was that he was going to fail miserably. But, he showed some great tenacity and turned the business around.

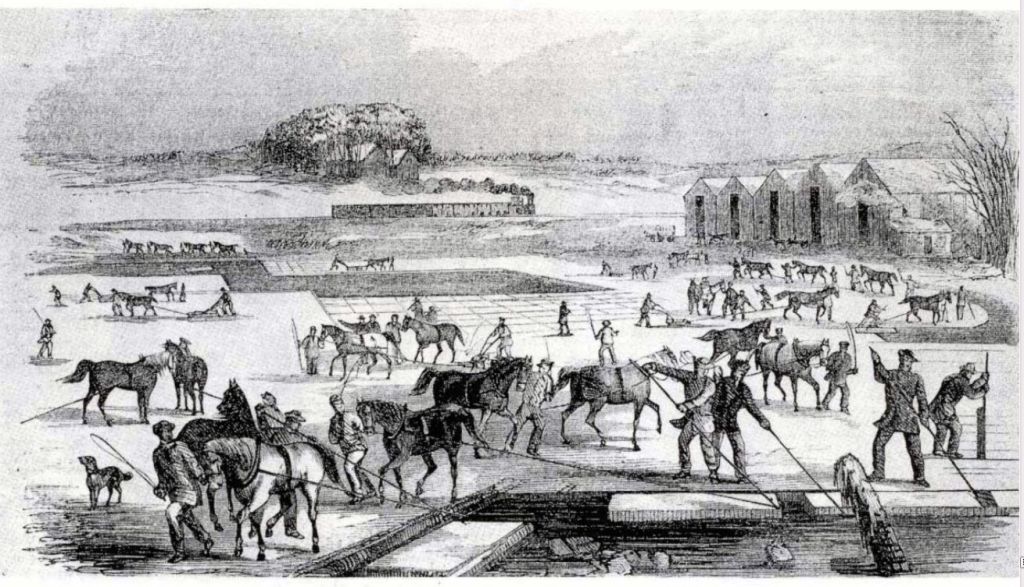

One of the key takeaways I had from Tudor was his incredible thrift. His resources were almost all free. The ice he sold was free, the sawdust that kept the ice from melting on long voyages was a free byproduct of large New England forestry companies, and the ships that returned empty to the warm climates after their shipments of sugar cane, coffee, tea, and cotton, weren’t free but heavily discounted.

Like many Silicon Valley software entrepreneurs today, Tudor practiced the ‘freemium’ model, and often gave his ice away for free in order to generate demand. Ice was rarely used in drinks in tropical climates at the time, but once folks from the tropics got their taste, the demand skyrocketed.

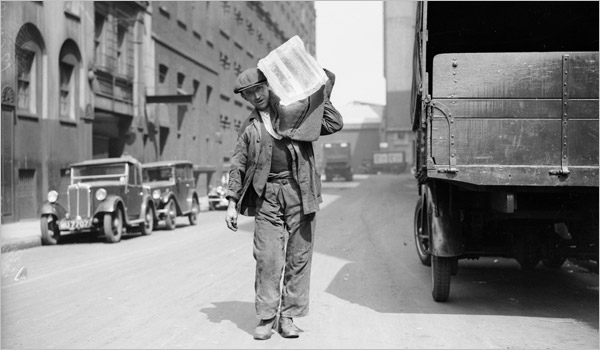

By 1850, Tudor was shipping 100k tons of ice per year or about 40 Olympic-sized swimming pools. He died at 80 years old with a net worth of over $200 Million dollars in 1864, and by the 1860s, two-thirds of Boston/New York homes also got daily ice deliveries influenced by Tudor. In an age when air-conditioning did not yet exist, demand for ice grew.

Not everyone was sold on the idea of ice at the beginning. Like many entrepreneurs, Tudor was building an industry that didn’t exist. When Tudor first started making trips to the Caribbean, British officials stopped him from doing business because they didn’t believe an ice business could exist. Tudor boldly asked Great Britain for a monopoly on the ice trade on the British islands of Barbados, Antigua, and Jamaica, which the British denied. In a genius move, Tudor changed his tone to make his business about promoting the health benefits of ice against tropical diseases such as Yellow Fever. The pitch worked, and he gained access to the markets.

The famous author, Henry David Thoreau, actually writes about Tudor’s ice business in “Walden”. Thoreau was rather bothered that the Tudor Ice Company interrupted his peace and quiet at the Walden Pond. Walden was one of Tudor Ice Company’s main repositories for export. But, Thoreau was impressed with the idea that “the pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges” as the ice would leave on Tudor Ice Company ships, cross the equator twice, and arrive for sale in Calcutta, India.

I believe Tudor got comfortable with the title of “Ice King” and eventually became resistant to change and innovation. He didn’t get married until age 50, when he married someone 30 years his junior and quickly had six children. Tudor should have seen the wave of air-conditioning coming, and he was perfectly positioned to own that market as well.

The first patent for air-conditioning came from an inventor in Florida named John Gorrie. However, rather than partnering with Gorrie, Tudor put out a ton of bad press against Gorrie and tried to kill his enterprise. It worked, and John Gorrie died a poor man. However, innovation from other competitors accelerated to accommodate demand, and Tudor’s Ice Company didn’t keep ahead of the innovation. In the late 1800s, export of ice completely died as an industry.

Tudor had to have been an incredibly ambitious man to think he could create an industry that likely hundreds had thought of before. I can imagine his work was extremely fulfilling as he brought something so useful to tropical areas that were rampant with disease and heat. I also think Tudor’s story is a good example of how a wealthy child with wild dreams could actually help the world.